|

Aidan Hickey

|

Through its many ups and downs, Irish animator Aidan Hickey has been at the forefront of the Irish animation industry for over thirty years. In this special IFTN interview, Aidan looks back upon his career to date and reveals his future plans for the first fully Irish animated feature film.

|

|

Aidan Hickey graduated from the NCAD with a degree in Painting in 1966. After working as an artist for a time, Aidan discovered his talents were better suited to animation and he became one of the first animators to work in Ireland. An animation contract with RTE and teaching kept his career on track into the 1990ís, but when that contract dissolved Aidan sought business elsewhere, building up contacts with animation studios across Europe, the US and Asia with whom he still works with today.

As an animator, scriptwriter, director and teacher Aidan Hickey has carved out one of the most admired and respected careers in the industry. His earlier award winning credits include ĎAn Inside Jobí (Winner of the Youth & Sports Prize, Annecy Festival 1987), ĎA Dogís Taleí (Best Animation Celtic Film Festival), ĎA Tale of Bawdryí (Feature Script Coup de Coeur Award, Annecy 1991) and ĎIf Youíd Believe This (Silver Pyramid, Cairo Childrenís Festival 1991). |

Working with Irish companies Hickey is behind some of the most successful Irish animated productions of late that include; ĎThe Island of Inis Coolí (Terraglyph), ĎHans Christian Andersení (Magma Films) and ĎThe Boy Who Had No Storyí (Brown Bag Films). His work with Korean studio OCON received a Special Mention Pulcinella Award at last monthís Cartoons on The Bay Festival and he also produced and wrote the Frameworks short ĎThe Popes Visití, which has just been selected for screening at the Anima Mundi Festival in Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo .

|

The Pope's Visit (2004) |

The animator still delights in his work as a producer, director and scriptwriter and with the 2004 Best Childrenís & Best Animation Irish Film and Television Awards under his belt, Hickey proves you can never be too old to capture the imagination of young children. Head of CARTOON Ireland since 1995, Aidan is currently developing his next ambitious project, the animated feature film ĎDiarmuid & Grainneí, with Telegael.

|

|

So Aidan, what was it about animation that first interested you?

In a way it developed out of the paintings I was doing, many of which were surrealist, and they became increasingly humorous. I remember we had an exhibition in the Gerry Davis Gallery in Capel Street. Adults looked at the paintings very solemnly but school kids came in on their lunch hour and fell about laughing at them. The joke had gotten through to them and that really pleased me. From that I got the idea that if I was going to make pictures that were funny, it would make more sense to do it on film, where you can get a pretty large audience, rather than the tiny audience youíd get in an art gallery. Plus, in a purely practical - almost cynical Ė notionÖ I wanted to draw and animation was the biggest single market for drawing I could think of. It uses thousands of drawings so I thought I could churn out drawings for the rest of my life and get paid for it.

There wasnít much of an industry back then, just you and a handful of other animators, had you any idea about how things would develop?

It was just a cottage industry at the time and it was very much a personal choice to get involved. I was aware of animation in the big bad world outside but it was never clear at all how we could slot into that. Opting for animation was a very isolating choice and I donít know how long I could have gone on with it, in that simple form.

Fortunately, during the 80ís I began going to festivals, like the Annecy Festival, to meet other people involved in animation. Then at the end of the 80ís the CARTOON organisation started and that made a huge difference. It linked people in all of the European countries together so that, rapidly, I knew somebody in every country who was involved in animation. And, very often, they were working on an equally small scale to what we were doing here. Things were a lot more comfortable from then on. |

An Inside Job (1987) |

How did that situation compare to how things are in Ireland today?

In some ways less favourable. I was fortunate, I guess, because back through the 80ís I had very good relations with people in RTE and I had an annual contract with them. I had to go out and justify it |

every year, by showing what I was going to do, but they gave me a reasonable income for what I was doing at the time. Even though it was much less than what was the norm in Europe for animation production, I was happy to do that.

By the end of the 80ís the market for short film series really died. Everybody started to do half-hours and that would mean producing 13.5 hours per year which was impossible in the studio that I had. Then RTEís attitude became much more commercial and I found I couldnít go on working for them. And nobody else ever got back into that comfortable position with them again. Nowadays RTE are notoriously difficult from an animation point of view. They rarely show an interest in indigenous animation projects. And the animation studios, generally, find it very difficult to deal with the situation there.

But, from another point of view, people with years of experience in the Bluth and Fred Wolf studios have a really deep knowledge and understanding of the craft and the business. The benefits of this are obvious among the younger generation. They have skills which go far beyond anything we could have hoped to have back in the 80ís. They are really solid professionals who have, I think, great potential for doing stuff into the future. I think from that point of view everything is much better and more optimistic than it was in the past.

Were you involved in the big studios like Sullivan/Bluth and Wolf?

I never had the slightest thing to do with Sullivan/Bluth. It completely passed me by. I just kept doing what I was doing when they came to Dublin. I was working almost always in cut paper animation, which was manageable for a small studio. I did very little regular drawing onto paper animation, so there really was no common ground between the two. Their projects were huge with massive budgets, and hundreds of people working on them. Apart from getting to know some of the artists and technicians who worked there, I never had any contact at all with the studio. Perhaps because they worked on TV series, I got closer to the people in Fred Wolfís studio. And they were among the first people I worked for, scripting, after I finished work with RTE.

What impact did their sudden closure have on the industry here?

Initially it was shocking. It really was a shattering blow - most obviously for the people who were working there. They had built their lives and careers around that work. Many of them had families and believed themselves to be in a secure and growing business. Then, suddenly it was all over. Of course many of them went to the States with Don Bluth. But, in the long run, there were benefits. The tough die-hards, who really wanted to do animation, and learned how to do it with both Bluth and Fred Wolf, have formed the core of the industry we have now.

They are people who know what theyíre doing, they love animation, they just want to do that and they keep finding better ways to do it. Theyíve built up very good contacts with people overseas, so there are a lot of links with Europe, increasingly with North America and also with the Oriental studios. I think itís fair to say that Irish animation is much more international than the rest of the Irish film industry, because of necessity. In the past we simply had to look elsewhere. I mean, for years and years I didnít work for anybody in Ireland. I wrote for studios in Germany, France, Denmark. Others were in the same position. That is the basis of this international linking thing that we have come to depend on.

Of course animation is much more easily sold to an international market?

Thatís true. Itís got a long shelf life and it goes on and on and on being broadcast in different countries. Obviously itís difficult to raise the money, as it is an expensive process, but nevertheless the return on it can be great and very satisfying.

|

The Boy Who Had No Story (2004) |

Do you think it is easier to get into the animation industry today?

I think itís pretty hard right now. I constantly get people sending me CVís that are truly impressive. I canít believe the knowledge and experience some people have acquired even at a very early age, but I always find it difficult to suggest anything that they can do. The number of |

studios here is small. The number of projects going through is also small and theyíre modest in scale. Itís very often quite difficult for youngsters to slot in. Nevertheless, many of them do and theyíre particularly successful within the 3D sector. Computer animation is changing things fairly dramatically for us all.

You still continue your work as a tutor with Screen Training Ireland, how satisfying is that for you?

Itís very satisfying. I only do scripting though, I donít do animation. Teaching scripting can be strange because you never quite know if the teaching has achieved its aim. Sometimes I think Iím better at organising teaching sessions for other people. One of the most memorable occasions I had with STI was when we brought Al Jean from ĎThe Simpsonsí organisation to Dublin. Those sessions were really excellent - for everybody involved, both the teachers and the students. Probably what made it so fascinating was realising how much power the writers have on ĎThe Simpsonsí. Their situation is unique in animation terms. I donít think that itís happened like that beforeÖ and itís unlikely to happen again.

How do you go about developing an idea?

Working with series, which I most often do, it depends on the bible thatís given to me by the production company. Stories always come out of character. I think thatís the classic way to workÖ and itís the way I always try to work.

Some of the more interesting projects Iíve done recently, like the one I am working on right now - the old Celtic legend of ĎDiarmuid & Grainneí, needed the characters to be built up first. Thereís an odd way in which mythical characters donít function all that well dramatically. Theyíre often at the mercy of such ďdeus ex machineĒ devices as the geasa. So we had to build up the characters, creating clear motivation for them. Then we could develop the storyís inherently strong dramatic arc. Itís a wonderful story on the page but, for a film story, the characters need to be the obvious source of the energy.

Is there a time when you say ďyes this is workingĒ, and do you do any test screenings of your work?

No, thatís very rare. Not since way back have I had the chance to do that. Itís one of the problems about permanently working on low budgets, as we do. The pressure is on to get the thing finished and out there as fast as possible and thereís a huge amount of wing-and-a -prayer sort of thing. You keep hoping that through instinct and experience you can deliver whatís required. You never quite know when the thing should be finished though. One of the problems with scripting is that you tend to go back to re-work it and re-work it, sometimes to the point of destruction. Maybe, very often, itís a good thing that the producer simply takes it out of your hands.

What do you like best about what you do?

To be honest itís the freedom to live in a fantasy world for half the week, just inventing strange things. Itís very enjoyable to create fantasy stories that, hopefully, kids will enjoy. And I certainly enjoy the process of putting such stories together. Itís also true that, over the years Iíve had to work with teams of people, usually far younger than myself, and Iíve found that a very positive and enjoyable experience. There is a team element involved in animation which I think is one of the big attractions for most people who work in the business. |

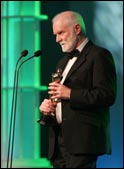

On Stage at the 2004 IFTA's

|

In 2004 you won a Best Childrenís and Best Animation IFTA for ĎThe Boy Who Had No Storyí, how important was that recognition for you?

For me personally it was huge, I really was happy. I must confess I hadnít won any prizes for years (laughs), I mean not since back in the 80ís. I was very fond of that project, I really liked the story and it was very nice to receive an award for it in Dublin. Itís based upon folk tales and therefore, theoretically, it has a big international connection but such stories are always very locally based.

|

The film has been shown at a lot of festivals and praised in various places around the worldÖ but it was particularly nice to get the award in Dublin.

How do you work in your studio?

Back in the 70ís I had a rostrum camera in a studio with three rooms; one room for drawing, one for the camera and one for sound and editing. The camera and editing room are completely idle now. In recent years itís simply a writing studio. Everybody works by email, so if Iím working for a studio in Germany or Korea I simply send the stuff off down the phone line.. Probably the biggest single change is that I donít do very much drawing anymore. I sometimes do storyboarding, but 95% of what I do is scripting and therefore itís just down to a computer and the scripting software.

Youíre still doing a lot of international work, do you find you get more work outside of Ireland?

No, well itís a curious thing because in the last two years Iíve worked much more in Ireland than I did before. There were many years when I didnít work in Ireland at all. At the moment Iím working on a project for Canadian television and Iím working with a script editor in LA. Iíve been doing some development work with a studio in Korea (OCON), but other than that Iím working with Magma and Telegael in Galway - and they are the two biggest projects Iím working on. I suppose the work is evenly divided now between Ireland and the other countries.

How familiar are you with the new digital methods of animation?

Iím familiar with what they can do. But if anyone asked me to actually do anything Iíd be completely lost. Working with the youngsters who have learned the stuff from college onwards is a great experience, because I can sit beside them and say Ďcould you do that and that thereí and they can do it instantly. Thatís like magic, watching it happen. Itís so clean and rapid in comparison with the terrible efforts we had to make years ago. As I say, I can understand it, and to an extent direct it, but I simply couldnít do it. Iím totally reliant on the people who have trained and have had experience of it.

Is there somewhat of a rivalry between the digital animators and traditional animators?

I think there has been a tension between the two. For a couple of years it was quite marked but, in a strange way, especially since Disney closed down their 2D studios, that tension has more or less evaporated. CGI animation, for the present anyway, has clear dominance. If you look at the box office results for films made in America, thereís almost no 2D animation that can match the success of The Incredibles, Shrek and the Toy Stories. So I think the 2D animators are in a slight huff at the moment. Thereís a general awareness that the later 2D animation films failed, very often, because of their stories. It wasnít the visual technique, it was just the lack of a good story. If the 2D films had the quality of story that John Lasseter at Pixar has insisted on, they would have been a hell of a lot more successful than they were.

I think the feeling is generally that these things go in cycles, and that, eventually, 3D will lose some of its novelty value and that things will get back to some kind of normality for 2D. But I doubt that it will ever again have the unique prominence it once hadÖ not least because of whatís happened at the Disney studios. An era has ended there.

|

So youíre somebody who welcomes the new technology?

Very definitelyÖif you think back to some of the torture we went through to achieve very simple effects with layers and layers of cell. Every layer of paint had to be carefully graded so that it allowed for how many cells would be over it. There were even simpler things - like keeping your finger marks off the cells - that slowed everything down.

|

The Island of InisCool (2002) |

Those were real chores that people had to deal with on a daily basis. Itís wonderful to have all of that taken away and see vastly richer effects created in a few minutes on a computer screen. For me, thatís all to the good. The creativity becomes much more important since the chores and laborious elements have been taken out of it.

Do you see the industry growing in Ireland over the next five years? Do you see it changing much?

I hope so. I mean, I feel pretty optimistic about it. An awful lot depends on being able to get the right kind of funding for projects - because we have a huge problem there.

The Film Board is goodÖ TG4 is supportive, but our big, permanent problem is not having the backing of the national broadcaster RTE. The animation group of SPI are in discussions with RTE at the moment and we are optimistic that changes will come about. But, the real difficulty is that, without the backing of the major broadcaster, itís impossible to access most of the financial support thatís on offer in the rest of Europe. If we can overcome that financial problem, Iím certain that, with the skills that are hereÖ with our use of the English language, which is a major advantage in animation terms, we have the potential to do an awful lot of really good production.

Can you see a repeat of the end of the Sullivan/Bluth era, with a lot of the animators going abroad to work?

I donít think so, I think this is whatís interesting about our situation now. The companies that have survived are very tight. Theyíve managed to stay compact and very flexible. So, they can increase in size if they need toÖ and if things get bad, they shrink back to a small core of people. Thatís a model that, I think, has great potential for survival and ultimately, I hope, for real prosperity.

There wouldnít be that mass exodus again, partly because there are simply not that many people working in animation. There are perhaps only 100 full time people working in the business now.

Do you think this is quite young personís game then?

Certainly the age profile is very young. Most people are around thirty or under, which by my standards is young. The business has such an insecure image that people do need a lot of courage and I guess youthful daring to get involved in it. Nevertheless I think itís possible as a career. Personally, I found it possible to live off animation, for all this time. But itís probably a choice for a limited number of people. I just donít knowÖ

Animationís image is one, universally, of youthful activity. On the other hand, there are people within it who have achieved remarkable longevity. Itís the kind of business that absorbs people, so they never want to leave itÖ and they just keep doing it.

There have been several attempts to establish an animation festival in Ireland, how do you feel about that?

I donít know if there is a big need for it, but there is certainly a strong ambition to do it. Some of the animation community in Kilkenny are making serious efforts to put a festival together there, next Autumn. That would be a first. In Dublin, it proved to be very difficult. In the city there are so many things going on that an animation festival tends to get buried. The Animation screenings in Galway each year are part of the Film Fleadh. And that works well. But, whatís proposed in Kilkenny could create an event with a clearer identity. If it develops its own character it could certainly benefit Irish animation.

But there are a huge number of animation festivals, all around the place, and itís very hard to get the right films and attract the right people to come and talk.

After working in the industry for so long, what ambitions have you now for the future?

One of my ambitions is to make a feature film of the kind that I am working on right now, the Diarmuid and Grainne story. I think that there has been a strange failure to make the Celtic legends into viable film stories up to now. They have great potential. Iíd like to be the first one to make such a filmÖ or maybe several such films! By Tanya Warren. |

|

|

|